Published by Fantagraphics Books. Due in stores in August. Pre-order at Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble.com, Borders.com, Subbooks.com, etc.

For those of you who are interested, Abandoned Cars will be premiering at the San Diego Comicon this July. I’ll be there on Thursday, Friday, Saturday & Sunday, sitting at the Fantagraphics table. Once I have the specific times, I’ll post them.

Abandoned Cars is my first collection of graphic short stories – the first in what I intend to build into a trilogy. Here’s what my publisher had to say about it:

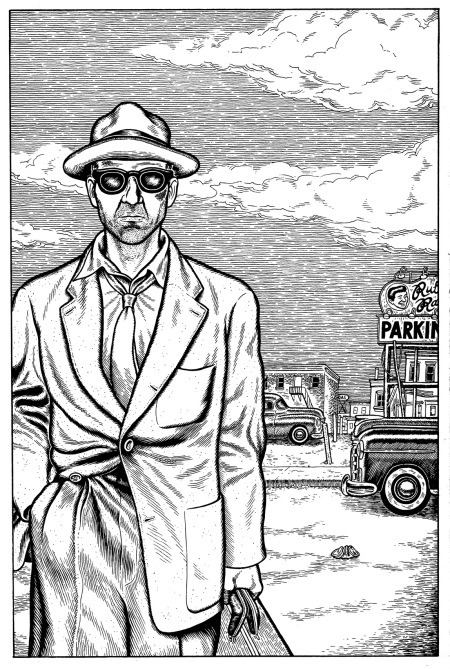

“Abandoned Cars is Tim Lane’s first collection of graphic short stories, noir-ish narratives that are united by their exploration of the great American mythological drama by way of the desperate and haunted characters that populate its pages. Lane’s characters exist on the margins of society—alienated, floating in the void between hope and despair, confused but introspective. Some of them are experiencing the aftermath of an existential car crash—those surreal moments after a car accident, when time slows down and you’re trying to determine what just happened and how badly you’re hurt. Others have gone off the deep end, or were never anywhere but the deep end. Some are ridiculous, others dignified in their efforts to struggle to make sense of, and cope with, the absurdities, outrages, ghosts, and poisons in their lives.

The writing is straightforward, the stories mainstream but told in a pulpy idiom with an existential edge, often in the first person, reminiscent of David Goodis’s or Jim Thompson’s prose or of films like Pick-Up on South Street or Out of the Past. Visually, Lane’s drawing is in a realistic mode, reminiscent of Charles Burns, that heightens the tension in stories that veer between naturalism on the one hand and the comical, nightmarish, and hallucinatory on the other. Here, American culture is a thrift store and the characters are thrift store junkies living among the clutter. It’s an America depicted as a subdued and haunted Coney Island, made up of lost characters—boozing, brawling, haplessly shooting themselves in the face, and hopping freight trains in search of Elvis.

Abandoned Cars is an impressive debut of a major young American cartoonist.”

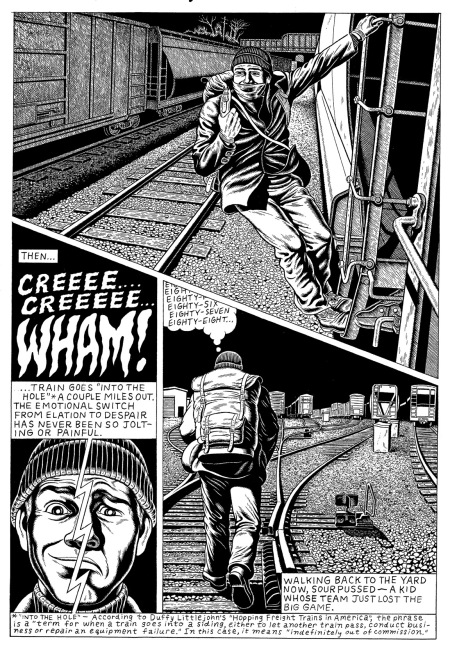

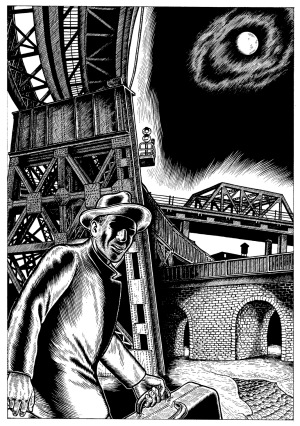

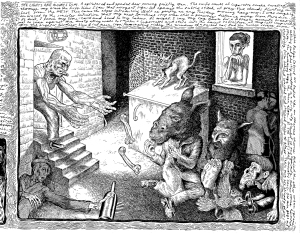

(Splash page: Spirit, Part One – Spirit is a three part graphic story documenting my first experience hopping freight trains. It’s the only story in the book that’s autobiographical. Although I prefer working with characters that I’ve invented, it was fun to include myself among the cast of characters that inhabit the landscape of the book.)

(Inside page: Spirit, Part One)

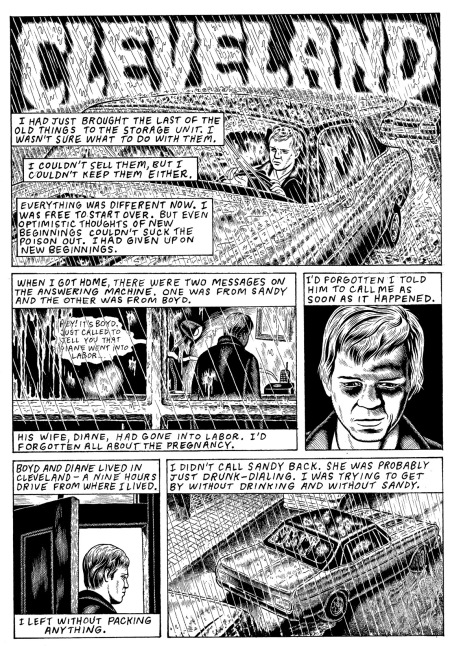

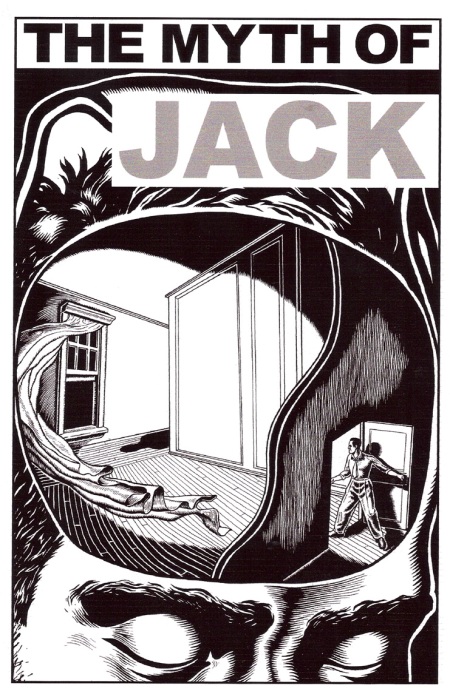

(Splash page: Cleveland)

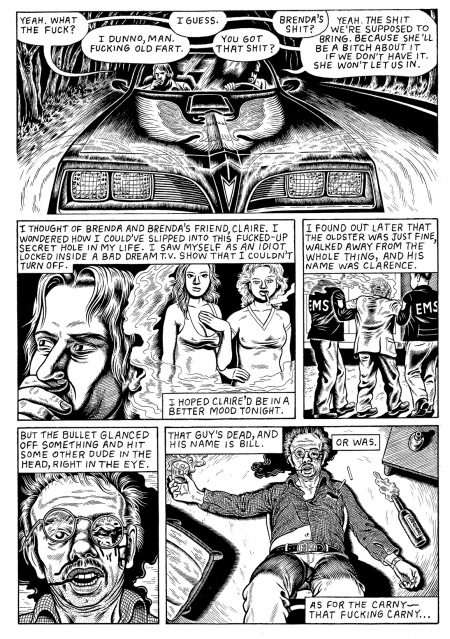

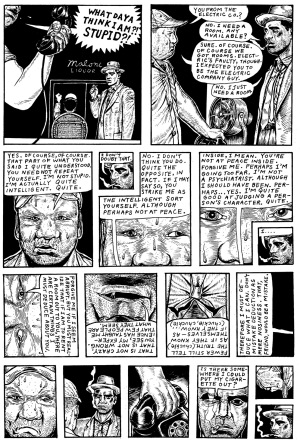

(Manic Depressive from Another Planet, Part Two)

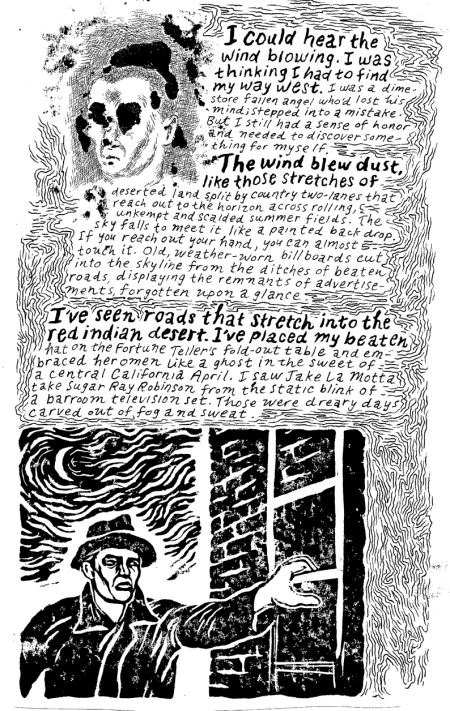

(Inside page: Spirit, Part Two – the point in the story when I have the honor of singing a delusional duet with the King of Rock & Roll himself)

(Inside page: Outing)

(Rockabillies: American Standard Cut-Out Collectible Series – In between graphic stories, there are a series of cut-out collectibles representing, I suppose, characters that populate the landscape of my mythological America. These characters are, incidentally, all real – in other words, they are not fictitious fabrications. Most of them first saw publication in a feature article in the St Louis alternative weekly newspaper, the Riverfront Times, which ran in the summer of 2006. They are an extension of a bigger project I’ve been playing around with for years – the creation of life size lawn ornament sculptures. The cut-outs are miniatures of the lawn ornament designs, and the miniatures are also available as lawn ornaments. I like the commercial, or “pop”, art aspect to lawn ornaments. Vehicles of artistic expression that are superficially regarded as low-brow or mass culture are, to me, very attractive. I feel very comfortable working with them (comics, of course, fit into this category). They are, on the surface, inoffensive and unintimidating. I think they’re also somewhat equalizing: They are a part of a cultural language we all understand, and no level of elevated academic/aesthetic knowledge is required for one to be able to “read” them. In this way, one can comment on society through it’s own language, making it accessible to everybody. That, to me, is important. And fun.)

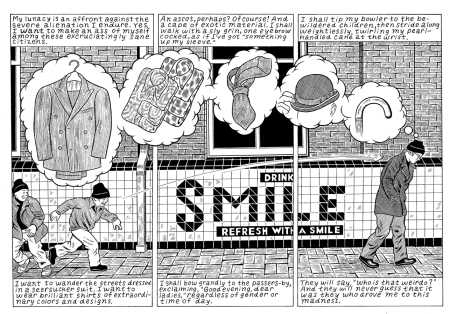

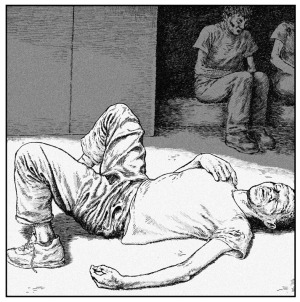

(“Manic Depressive/Notes of a Second Class Citizen” vignette – In between the longer graphic stories are a series of “graphic vignettes” documenting the slow mental breakdown of an ostensibly anonymous character – anonymous, in that he never reveals his identity. He is, in fact, the same character as the one you’ll see in the Manic Depressive from Another Planet, Parts One & Two. This series was also first published as a series in the Riverfront Times, under the title “Notes of A Second Class Citizen”. The influence was Dostoyevski’s anonymous anti-hero in Notes from Underground – a book that has been one of my favorites since I was a teenager. But it is as much influenced by The Marx Brothers as it is Dostoyevski.)

(“Manic Depressive/Notes of a Second Class Citizen” vignette

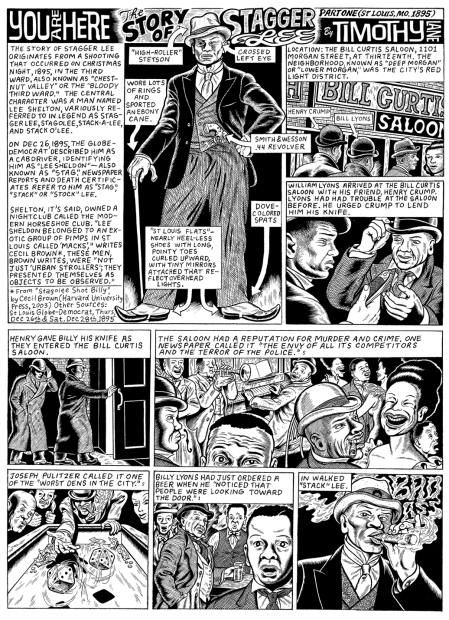

(Splash page: Story of Stagger Lee: The only historical story in the book.)

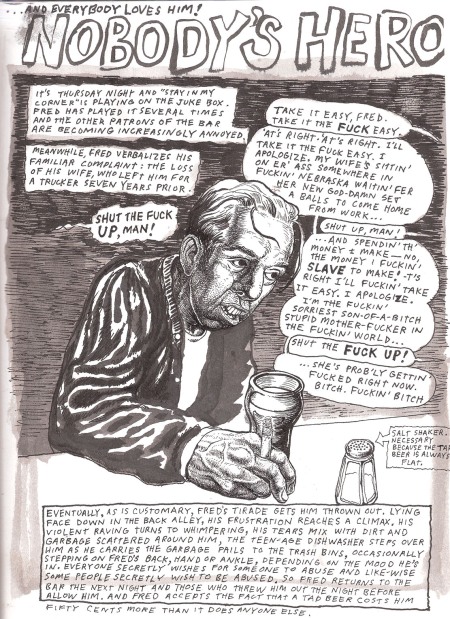

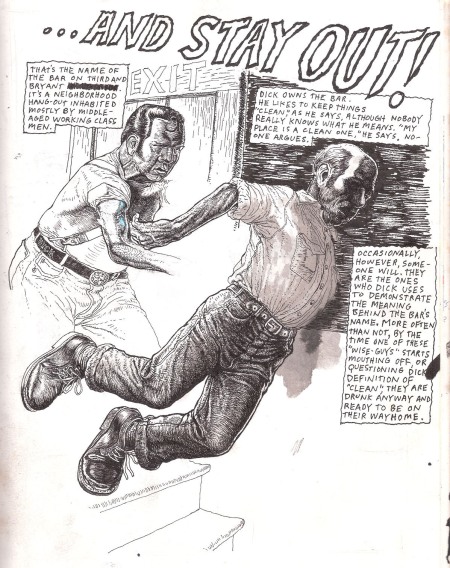

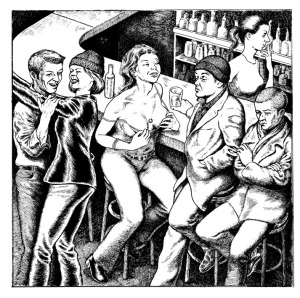

Below are sketchbook drawings scribbled around 1994-1996, between the times I was living in Minneapolis, MN and San Francisco, Oakland, and El Cerrito, CA. I’m posting them because they are the first evidence of the work that would later become Abandoned Cars. While in Minneapolis, I was working as a bartender at a bar that was owned by a guy named Dick. The bar was a dive, completely. The characters depicted below are all influenced by my recollections of the nightly clientelle.

(Nobody’s Hero, drawn around 1994-95)

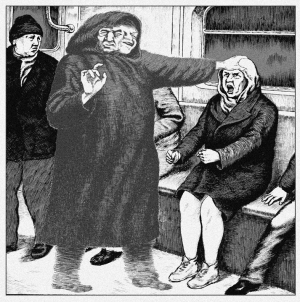

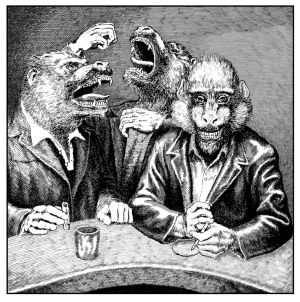

(Russ & Pip – these two guys were old high school friends whose strange habit it was to do the nightly rounds of neighborhood bars in each other’s company, slowly getting on each other’s nerves, until finally one of the two went too far with a snide comment or dismissive gesture. Next stop: out to the street or back alley to have it out. Nothing serious ever really came of it, although once “Russ” pulled “Pip” off his bar stool by pulling him from behind by the collar, sending Pip crashing to the ground headfirst – just dropped like a big sack of flour; did nothing to brace his fall. He cracked his head pretty good, and after being taken to an emergency room, his wife – and a real piece of work, she was – came looking for him (women were always looking for their husbands or ex-husbands or boyfriends or whatever. They were pretty close to the only female clientelle the bar regularly had) and when she found out what had happened, all she could do was bitch about the fact that Pip hadn’t fed or walked their dog.

(…And Stay Out!)

(Phil: The speech balloons on the left hand size of the panel are meant to be the voice of phil’s wife.)